Education

WALES: The student who became a Welsh bard at 19

WALES: An Indian student won acclaim in Wales as a bard and became the first woman to get a law degree from University College London. And although racial prejudice brought a heartbreaking end to a three-year relationship she never went home, writes Andrew Whitehead.

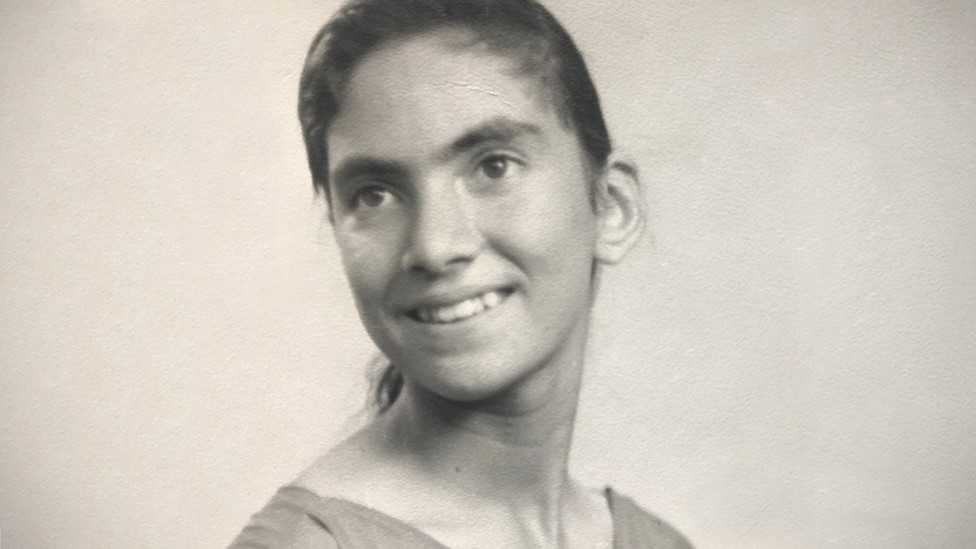

Dorothy Bonarjee was Indian by birth, English by upbringing, French by marriage – and Welsh at heart.

To put it another way, she was the perpetual outsider, sometimes by chance, and at other times by choice. Even the moment of her greatest achievement in 1914 – winning one of Wales’s most prestigious cultural prizes while still a teenager – is notable above all because she was so obviously not Welsh.

In India, Dorothy Bonarjee and her family stood apart, by class, culture and religion. They were upper-caste Bengali brahmins, but Dorothy spent her childhood living a simple life on the family estate hundreds of miles away from Bengal in Rampur, near India’s border with Nepal. They were also Christians – her grandfather served as a Scottish pastor in Calcutta (now Kolkata) after being converted by celebrated Scottish missionary Alexander Duff.

Dorothy’s life changed utterly in 1904 when – along with her brothers, Bertie and Neil – she was sent to London for her schooling. She was just 10 years old.

Dorothy’s parents – both of whom had spent time in Britain – wanted their children to be, like them, part of the “England returned” who were increasingly running India on behalf of the imperial power.

Among the Indian elite, this British experience had “something of the snob value of a peerage in Great Britain,” one of the Bonarjee clan remarked.

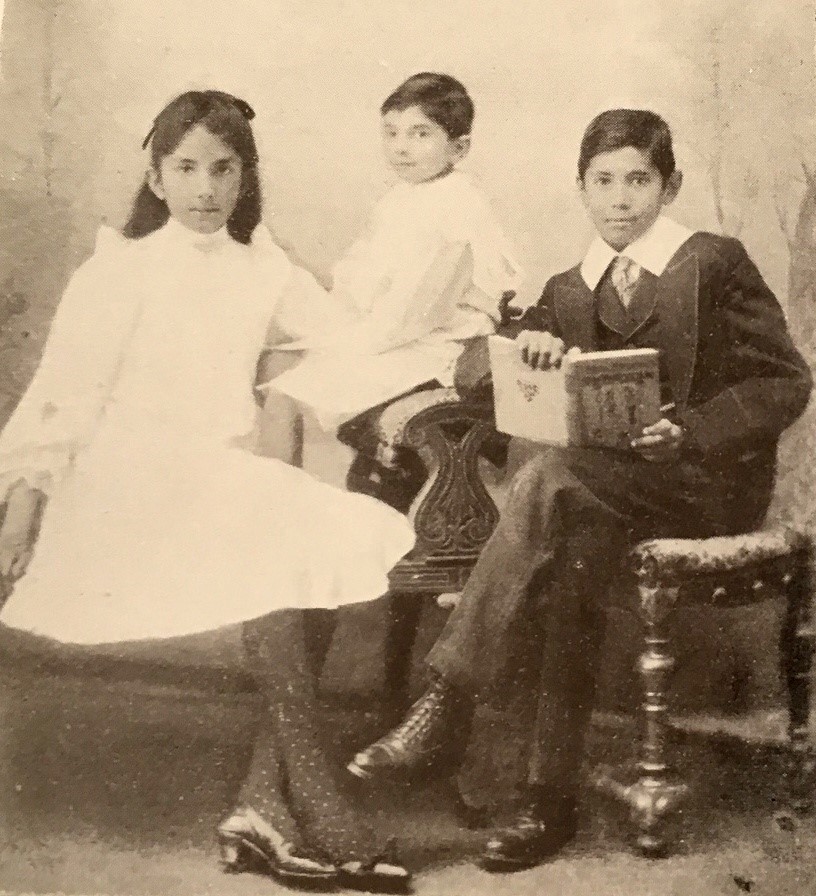

A photograph survives of the three young Bonarjees at about the time they arrived in London. Dorothy looks demure in a white dress with a black ribbon in her hair. Bertie, her older brother, is in a suit and tie. It’s a statement of how English they had become – even though the world around would always see them as Indian.

Dorothy’s father was a barrister as well as a landowner. She was probably closer to her mother, who was a strong advocate of girls’ education. Both daughter and mother were active supporters in Britain of votes for women. And thanks to her mother, Dorothy had a privilege rare in either Britain or India a century ago – she was going to get an education just as good as her brothers.

“At the time of the First World War, there were about a thousand Indian students at British universities,” says Dr Sumita Mukherjee at the University of Bristol, who has written a book about “England returned” Indians. “Around 50 to 70 of these would have been women.”

In 1912, Dorothy Bonarjee joined this select group. The family had expected Dorothy to go to the University of London. But according to family folklore, she found London too “snobbish” and so opted instead for the University College of Wales in the largely Welsh-speaking seaside town of Aberystwyth.

“Where the hell is that?!” her father is said to have exclaimed. But Dorothy got her way. And her brother Bertie also enrolled there – in part to serve as his sister’s chaperone.

Dorothy’s decision may well have been shaped by the progressive reputation of the college. “A major foundational principle for the establishment of the University College at Aberystwyth was that all religious persuasions and cultural backgrounds were welcome,” says Dr Susan Davies, an archivist and historian at what is now Aberystwyth University.

And the college, the oldest of three forming the University of Wales, also had an impressive record in gender equality. By the time Dorothy arrived there, approaching half the students were women, a much higher proportion than at most British universities at this time. By the time of her graduation ceremony in 1916 – when many of the men were fighting in Flanders and France – women were in a clear majority.

Dorothy was clearly a popular student, taking a prominent role in the literary and debating society and helping edit the college journal. Her big moment came in February 1914 at the college’s annual Eisteddfod, a pageant and celebration of Welsh culture in which writers and musicians competed for prizes. While this was not as prestigious as the national Eisteddfod, it was a major cultural event in the country’s Welsh-speaking heartlands.

Entrants for the main competition, poetry in the traditional Welsh style, had a chance to win an imposing hand-carved oak chair. All poems were submitted under pseudonyms. A Welsh newspaper, the Cambria Daily Leader, reported on its front page under the headline Hindu Lady Chaired the “remarkable” scenes when the winner was announced:

The highest place was awarded to ‘Shita’, for an ode written in English, and described as an excellent and highly dramatic treatment of the subject… Miss Bonarjee received a deafening ovation when she stood up and revealed herself as ‘Shita’. She was led up to the throne… The ‘chairing’ ceremony then proceeded amidst great enthusiasm.

Dorothy’s parents were present to see their 19-year-old daughter’s success. Her father was prevailed upon to address the crowd, thanking them for the way they had “received a successful competitor of a different race and country”. If India had given birth to a poet, he declared, Wales had educated her and given her an opportunity to develop her poetic instincts.

Dorothy Bonarjee was the first foreign student and the first woman to triumph at the college Eisteddfod. This was a landmark achievement – the first woman to win the chair at the national Eisteddfod came as recently as 2001.

Emboldened by her success, she contributed poems to journals including The Welsh Outlook, a monthly magazine reflecting and encouraging Welsh cultural nationalism. Even after she left Wales, she continued to publish there.

“She loved the Welsh,” says her niece Sheela Bonarjee. “She couldn’t speak Welsh – so she was always an outsider in that sense. But they did accept her.”

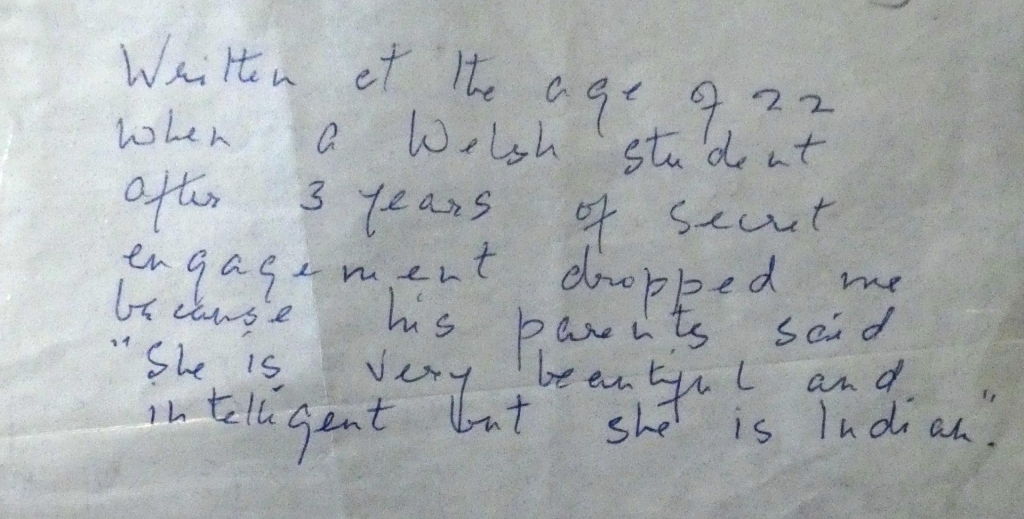

However, Dorothy endured heartbreak at Aberystwyth as well as acclaim. Sheela Bonarjee still has the battered black exercise book in which her aunt collated her verse. Alongside one of the poems, Dorothy jotted down a note: “Written at the age of 22 when a Welsh student after 3 years of secret engagement dropped me because his parents said ‘She is very beautiful and intelligent but she is Indian.'”

“It destroyed her. She was distraught,” Sheela says, recalling the confidences her aunt shared about that failed romance. “There’s a poem of hers that shows the loss of that boyfriend.” That poem is called Renunciation:

So I must give thee up – not with the glow

Of those who losing much yet rather gain.

But losing all. Did never martyr go

Along the bleeding road of useless pain?

Did never one held prisoner by a creed,

Obsessed by stern heroic ghosts, made dumb

By those who answered duty to his need,

With faithless loathing feet to his fate come?

Dorothy had got used to being the outsider but there could be a painful price to pay for being different.

Her younger brother, Neil, later studied at Oxford – and came across a wall of prejudice there. “Indians in general, it must be said, along with other coloured races were not popular in the University,” he wrote. His English fellow students “had something which I had not, namely an Empire. They possessed, while I only belonged.”

Dorothy was undaunted. From Aberystwyth, she and Bertie returned to London where both took a second degree course. Again, she was a trailblazer – the first woman student at University College London to be awarded a law degree. The family then expected the youngsters to return and make their lives and careers in India. Her brothers dutifully got on the boat. Dorothy rebelled.

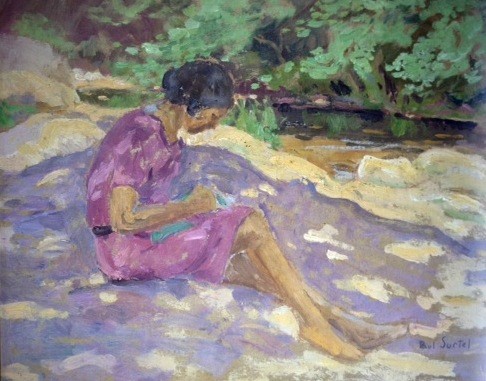

She was caught between different cultures and social values. She was free-spirited and committed to women’s equality – not someone who would easily consent to a marriage arranged by her family in India. So she eloped with a French artist, Paul Surtel.

Her father was furious; her mother seems to have been more understanding. The couple married in 1921, and settled in the south of France. While Surtel gained distinction as a painter, his wife largely retreated from public view. They had two children, one of whom died in infancy, but by the mid-1930s the marriage was over. “Nothing is more wearing morally,” Dorothy commented, “than a weak husband.”

Her family pleaded with her to return to India. Once again she refused – a decision she seems later to have regretted. Her father eventually bought her a small vineyard at Gonferon in Provence to serve as both home and livelihood. Money was tight. This was not the life of ease she might have hoped for. She never remarried.

Sheela Bonarjee followed in her aunt’s footsteps from India to London in the 1950s, and made several visits to the south of France. She remembers her “Auntie Dorf” as elegant, confident and unconventional. In some ways she was very French, Sheela recalls. “She had wine with every meal, which for me as an Indian was very strange and at times I wondered why I was so sleepy all day.” But she spoke French with a pronounced accent.

Dorothy Bonarjee kept in touch with her Welsh friends all her life. In her old age, she paid a pilgrimage to her old university. “I went with her to Aberystwyth – that must have been in her 80s,” Sheela Bonarjee recalls of a trip more than 40 years ago. “It was an important visit for her – to have her memories.”

She now has the distinction of a place in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, the only person of Indian origin among almost 5,000 entries. It’s written by Dr Beth Jenkins of the University of Essex. “Dorothy certainly embraced Welsh national culture,” she argues, “and contributed significantly to it during her time in Aberystwyth.”

Dorothy lived to almost 90. But she never set foot in India again after leaving as a young girl. The Indian side of her remained important, though. On high days and holidays she would delight her French neighbours by dressing up in a sari. But she was in many ways more French, more English, perhaps even more Welsh, than she was Indian. And everywhere, she was always the outsider.

When a health emergency prompted Nathan Romburgh and his sisters to look into their family history, decades after the end of apartheid, they uncovered a closely guarded secret that made them question their own identity.

Education

LONDON: 3 Indian-Origin Candidates Shortlisted For Oxford Chancellor’s Post, Imran Khan Out

LONDON: The University of Oxford today announced the final candidates for their Chancellor election. Three Indian-origin individuals are among the 38 finalists, but former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan was not included.

Diverse Field Of Contenders

The finalists come from various backgrounds including academics, politicians, and business leaders. Ankur Shiv Bhandari (first Indian-origin Mayor of Bracknell Forest), Nirpal Singh Paul Bhangal (Professor of International Entrepreneurship), and Pratik Tarvadi (medical professional) will be competing for the position.

Former Conservative Party leader Lord William Hague and former Labour politician Lord Peter Mandelson are among the senior politicians selected, however, Khan is deemed to have been disqualified following the selection process.

38 Candidates Meet Tough Criteria

“Applications were considered by the Chancellor’s Election Committee solely on the four exclusion criteria set out in the university’s regulations. All applicants have been notified whether their submissions have been successful,” a university statement reads.

To qualify for the unpaid position, candidates were required to meet stringent criteria. They had to demonstrate exceptional accomplishments in their field, as well as the ability to inspire respect from a wider audience.

Additionally, candidates were expected to have a profound understanding of the university’s research and academic goals, its diverse global community, and its aspiration to maintain its status as a world-class institution. Furthermore, they needed to possess the capacity and desire to elevate the university’s reputation both domestically and internationally.

Although the university did not provide specific reasons for individual rejections, some experts suggested that Khan’s criminal convictions in his home country – Pakistan, might have disqualified the former Oxford graduate.

The University’s Convocation, composed of faculty and alumni, will now conduct an online election to choose Lord Patten’s successor. Lord Patten, a former governor of Hong Kong, will step down from his 21-year tenure as Chancellor at the end of Trinity Term 2024.

In the first round of voting, which begins on October 28, voters can rank as many candidates as they wish. The top five candidates, to be announced on November 4, will advance to the second round of voting, scheduled for November 18. The University of Oxford’s new Chancellor will be revealed on November 25.

In his ‘Statement of Interest,’ Mr Bhandari expressed his desire to become Chancellor of Oxford University. He described the university as ‘a temple of learning, research, and a beacon of history’ and stated that serving as Chancellor would be ‘the honor of my life.’ Mr Bhandari believes he is well-suited for the role and can contribute to the university’s ongoing mission.

Mr Bhangal highlights his global connections, deep understanding of Oxford and Oxford University, and experience as a course developer and visiting professor. He believes his strong business acumen, multicultural competence, and government contacts in major economies worldwide make him a valuable asset to Oxford University in the 21st century.

Tarvadi sees the Chancellor position as an opportunity to promote inclusivity, innovation, and a global impact. He asserts that his international experience and network would be crucial in establishing new partnerships and strengthening existing ones, thereby ensuring Oxford’s continued leadership in global academic and research endeavors.

Oxford Chancellor – A Decade Of Leadership

The incoming Chancellor will serve a fixed term of no more than 10 years, in line with recent amendments to the university’s statutes.

The Chancellor serves as the ceremonial head of Oxford University, presiding over significant ceremonies and chairing the Committee to Elect the Vice-Chancellor. Beyond these formal responsibilities, the Chancellor engages in advocacy, advisory, and fundraising activities, representing the university at various national and international events.

The position of Chancellor has previously been held by former Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan, former Labour home secretary and president of the European Commission Roy Jenkins, and most recently by Lord Patten.

Education

WASHINGTON: Two Indian Americans Appointed To Class Of White House Fellows

WASHINGTON: Two Indian Americans, Padmini Pillai from Boston and Nalini Tata from New York, were appointed to the 2024-2025 class of White House Fellows on Thursday.

In all, 15 exceptionally-talented individuals from across the United States have been named to this prestigious programme. Fellows spend a year working with senior White House staff, cabinet secretaries and other top-ranking administration officials, and leave the administration equipped to serve as better leaders in their communities.

While Ms Tata is placed at the White House Office of Cabinet Affairs, Padmini Pillai is placed at the Social Security Administration, the White House said in a media release.

Newton, Massachusetts, Ms Pillai is an immunoengineer bridging the gap between discoveries in immunology and advances in biomaterial design to treat human disease.

She has led a team at the MIT developing a tumour-selective nanotherapy to eliminate hard-to-treat cancers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms Pillai was featured in several media outlets, including “CNBC”, “The Atlantic” and “The New York Times”, to discuss vaccination, immunity and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on vulnerable communities.

Ms Pillai received her PhD in immunobiology from the Yale University and a BA in biochemistry from the Regis College.

Ms Tata is a neurosurgery resident at the New York-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Centre/Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre, where she helps treat the spectrum of emergency and elective neurosurgical conditions between a level-1 trauma centre and a world-renowned cancer institute.

Her published work spans clinical and non-scientific journals, with a focus on advancing equity in access to care. Her career in neurosurgery and long-standing interest in public policy are closely bound by a deep-rooted dedication to public service. She received her BSc in neurobiology from the Brown University, MPhil from the University of Cambridge, MD from the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine and MPP in Democracy, Politics, and Institutions from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

According to the White House, this year’s Fellows advanced through a highly-competitive selection process, and they are a remarkably gifted, passionate and accomplished group. These Fellows bring experience from across the country and from a broad cross-section of professions, including from the private sector, state government, academia, non-profits, medicine and the armed forces, it said.

Education

NEW YORK: Indian-American Professor Researching Dalit Women Gets $8,00,000 “Genius” Grant

NEW YORK: An Indian-American professor, Shailaja Paik, conducting research on and writing about Dalit women has received a $800,000 “genius” grant from the MacArthur Foundation which gives out awards every year to people with extraordinary achievements or potential.

Announcing her fellowship, the Foundation said, “Through her focus on the multifaceted experiences of Dalit women, Paik elucidates the enduring nature of caste discrimination and the forces that perpetuate untouchability.”

Ms Paik is a distinguished research professor of history at the University of Cincinnati, where she is also an affiliate faculty in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and Asian Studies.

“Paik provides new insight into the history of caste domination and traces the ways in which gender and sexuality are used to deny Dalit women dignity and personhood,” the Foundation said.

The MacArthur Fellowships, popularly known as “genius” grants, are given to people across a spectrum from academia and science to arts and activism, who according to the Foundation are “extraordinarily talented and creative individuals as an investment in their potential”.

The selections are made anonymously based on recommendations received and it does not allow applications or lobbying for the grants, which come without any strings and are spread over five years.

The Foundation said that her recent project focused “on the lives of women performers of Tamasha, a popular form of bawdy folk theatre that has been practised predominantly by Dalits in Maharashtra for centuries”.

“Despite the state’s efforts to reframe Tamasha as an honourable and quintessentially Marathi cultural practice, ashlil (the mark of vulgarity) sticks to Dalit Tamasha women,” it said.

Based on the project, she published a book, “The Vulgarity of Caste: Dalits, Sexuality, and Humanity in Modern India”.

It said, “Paik also critiques the narrative of Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the twentieth century’s most influential caste abolitionist” and the architect of India’s Constitution.

In an interview with National Public Radio (NPR), the US government-subsidised broadcaster, she said that she was herself a member of the Dalit community who grew up in Pune in a slum area and was inspired by her father’s dedication to education.

After getting her masters’ degree from the Savitribai Phule University in Pune, she went to the University of Warwick in the UK for her PhD.

She did a stint as a visiting assistant professor of South Asian history at Yale University.

Since the programme began in 1981, fellowships have been granted to 1,153 people.

Previous MacArthur Fellows include writers Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, and Ved Mehta, poet A.K. Ramanujam, economists Raj Chetty and Sendhil Mullainathan, mathematician L Mahadevan, computer scientists Subhash Khot and Shwetak Patel, physical biologist Manu Prakash, musician Vijay Gupta, community organiser Raj Jayadev, and lawyer and activist Sujatha Baliga.

-

Diplomatic News1 year ago

Diplomatic News1 year agoSTOCKHOLM: Dr. Neena Malhotra appointed as the next Ambassador of India to the Kingdom of Sweden

-

Technology2 years ago

Technology2 years agoMARYLAND: All About Pavan Davuluri, New Head Of Microsoft Windows

-

Opinions5 years ago

2020 will be remembered as time of the pandemic. The fallout will be felt for years

-

Diplomatic News1 year ago

Diplomatic News1 year agoKINGSTON: Shri Subhash Prasad Gupta concurrently accredited as the next High Commissioner of India to St.Vincent and the Grenadines

-

Politcs2 years ago

Politcs2 years agoLONDON: Indian-Origin Candidate On How He Plans To Win London Mayoral Polls

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoSINGAPORE CITY: Indian Wins Big In Singapore Company’s ‘Squid Game’ Survival Contest

-

Health1 year ago

Health1 year agoWASHINGTON: Social Media Has Direct Impact On Mental Health- US Surgeon General To NDTV

-

Science2 years ago

Science2 years agoWASHINGTON: Who Is Aroh Barjatya, Indian-Origin Researcher Who Led Recent NASA Mission